Seven Not-So-Modest Proposals to Improve the Political Process

But as our “Lords and Masters” must legislate them, don’t hold your breath . . .

1. Appoint your own representative. Shareholder style.

In theory, you are represented in parliament by the person elected in your electorate.

But what if you didn’t vote for him or her? Do you feel you’re truly represented?

But what if you didn’t vote for him or her? Do you feel you’re truly represented?

Can you withdraw your representation? Of course not. You’re saddled with whoever it is until it’s election time again. (And probably afterwards too.)

I don’t know about you, but I’d much rather choose my own representative than be stuck with someone I neither like nor agree with just because I live in a specific geographic area.

How about switching parliamentary representation to the company “proxy model.”

When you own shares in a company, you can either represent yourself and vote those shares at a general meeting or appoint someone to vote on your behalf. Specifying whether it’s “yeah” or “nay” on each specific issue.

Given today’s technology, there’s no reason why that model cannot be applied to parliament. (Companies use it all the time. It works.)

Elections as we know them would disappear. Instead, would-be representatives would seek our proxy. A proxy that could come from a voter in any part of the country instead of a specific geographic area; a proxy we could withdraw, switch or restrict at any time.

Assuming the number of members of the parliament remains unchanged, the members elected would be those with the most proxies. In the US House of Representatives, for example, the top 435.

But, as we can simply login and switch our proxies at any time, those 435 members won’t necessarily sit in the House until the next election.

Or even the next day!

Say we gave our proxy to Bloggs who was the 435th elected ’cause we figured he was a good guy. But it turns out he’s a charlatan. If enough other people think the same way, Bloggs would be thrown on his arse and replaced by Smith—who was number 436. No need to wait until the next election, or organize a recall, if such an option is available to you.

Or, if Bloggs was generally okay but you disagree with him strongly on a particular issue—whether it be climate change, abortion, same-sex marriage, or whatever—you could give your proxy on that specific issue to Jones, or someone else who agrees with you.

That’d sure as hell keep those pollies on their toes—and make “representative democracy” truly representative!

2. Referendums: When “We the People” Speak—and are Heard!

Supposedly, in a democracy, we the people are the rulers.

The reality is somewhat (actually quite, quite) different. Every two to six years, depending on where you’re living, you get to cast a vote. Usually, we have only two choices, thanks to the way the political process works.

The aim of every political party is to secure a majority of the parliament or congress, which enables it to rule. Sometimes, a coalition of two or more parties is needed to create a parliamentary majority.

Either way, as voters our effective choice is severely limited.

Switzerland offers a somewhat different model: the referendum.

If just 110,000 Swiss citizens—a mere 1.85% of registered voters—object to a law, they can call for a referendum. If a majority votes against the law, it becomes null and void.

That same (or another) 100,000 citizens can propose an issue for a referendum.

In Switzerland, the people can easily overrule the politicians.

Under the Swiss model, the pollies don’t always get their own way.

In 1974 I met a Swiss banker in Sydney who commented that he had always thought there were just far too many referendums in Switzerland.

Until he came to Australia.

Two years earlier the Labor Party had won the federal election after 23 years in the wilderness of Opposition. Led to victory by the charismatic Gough Whitlam, the Labor government tried to squeeze 23 years’ worth of what it believed were much needed reforms into just a year or two.

The result was destabilising and unnerving for too many people.

Had the Swiss model prevailed, many of those reforms would have been rejected by the voters—and Gough might have been re-elected instead of being thrown out of office.

3. Anyone Who Volunteers Him- or Herself for Public Office Should Be Automatically Barred

For life.

Politics attracts people who like to have power over others. Those others being us.

That doesn’t apply to everyone who enters the political arena. Some are idealists who want to change the world; but as a generality the pragmatists whose main focus is reelection tend to rise to the top.

Politicians tell us they’re there to “serve the greater good.” If that’s really the case, they should be happy to ban any power-luster who is, after all, only out to serve him- or herself—at everybody else’s expense.

If volunteering for any political office is banned, those who really want the job will have to find a way to get themselves “drafted” by others. Which raises an interesting question: would anyone who really doesn’t want the office accept it if offered?

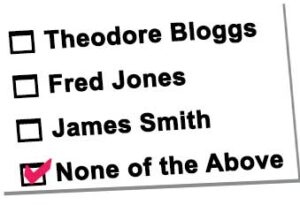

4. Add Another Option: “None of the Above”

Current voting systems all around the world offer you a limited choice: limited to the number of candidates on the ballot paper.

What if you would not vote for any of them? Well, you can always stay at home.

How about having another option to the ballot paper: “None of the Above”?

Which would make little difference to the results unless 50% of the vote plus one, including “None of the Above” votes, was required to win.

Unless—as one comedian put it—”None of the Above” was at the top instead of the bottom of the ballot paper.

A joke—but just the sort of thing some politicians would certainly prefer!

5. Election by Phone Book?

National Review founder William Buckley once said he’d rather be ruled by the first 100 names in the New York telephone directory.

Not a bad idea . . . to start with.

Look at a phone book (if you can find one nowadays) and you’ll see that it begins with listings like AAA1 Repairs and AAAA1 Repairs.

By the time of second or third “phone book election,” I’ll bet that hopeful pollies will have all legally changed their names to, f’rinstance, Donald AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAATrump!

6. Preferential Voting

This system of voting, currently used only in Australia, Fiji, and Papua New Guinea on a national scale, is a simpler form of the more popular “run-off” election: When no candidate has 50% plus one of the vote, a second election is held with just the top two candidates on the ballot.

When there are just two candidates, whoever gets the most votes wins.

But with three or more candidates, preferential voting starts to get interesting.

Preferential voting means numbering all the candidates in order of your preference. So if Bloggs, Jones and Smith are the candidates, and you want Jones to win but detest Smith, you might vote like this:

1 Jones

3 Smith

The winner has to get fifty percent of the votes, plus one.

When the votes are counted only the first preferences—the 1s—are tallied. Say the count looks like this:

Jones 27

Smith 44

TOTAL 100

In countries like the U.S. and Britain with a “first past the post” system, Smith would be the winner—even though a majority of 56% voted against him.

But with preferential voting, since Smith does not have fifty percent of the votes plus one, there’s a second round: the preferences of the lowest candidate are “distributed.” In this case, that’s your candidate, Jones.

All his votes are counted again. But this time the 2s, not the 1s, are tallied. Those 2s are added to Bloggs’ and Smith’s 1s to give the final total. Let’s say 5 Jones voters put Smith as their second choice, while the other 22 went for Bloggs. The final result is:

Smith 49

TOTAL 100

So even though Jones, your favorite candidate, didn’t make it, at least that charlatan Smith didn’t get in—because your vote was counted twice.

When there are more than three candidates—as always happens in the Australian Senate polls—the process is the same if a little more complicated. They simply keep distributing preferences until they reach “the last politician standing.”

One downside is called the “Donkey Vote”: voters who simply number the candidates 1, 2, 3, 4, . . . from top to bottom. That can add up to 4% to the candidate whose name is first on the list.

Preferential voting comes in two forms—you have to number all the candidates, from 1 to wherever. Or you can number as many or as few as you like.

Preferential voting might have changed the result in the US 2016 presidential election.

Trump won the electoral votes, but his national vote of 46.09% trailed Clinton’s 48.1%. Of the other parties, Libertarians won 3.28%, while the Greens achieved 1.07%.

According to a CBS News exit poll, in a two-candidate race 25% of Libertarian voters would have voted for Clinton, 15% for Trump, and 55% would have stayed home. The similar numbers for the Greens were 25% Clinton, 14% Trump, and 61% said they wouldn’t bother voting at all.

Preferences would increase Clinton’s vote total over Trump from 48.1%/46.09% to 49.19%/46.73%.

Not a big increase in Clinton’s margin. But possibly enough to change the result in one or two states, so increasing her electoral vote total. Though unlikely by enough to close the gap of 74 between her 232 electoral votes to Trump’s 306.

In 2020, when Biden won 51% of the national vote, making him the clear winner: preferential voting wouldn’t have changed that. Unless the “vote-againsters”—those didn’t vote for but against Biden or Trump—registered their distaste for both major candidates in sufficient numbers by giving their first preference to one of the minor parties or independent candidates.

7. Let’s Have Some Results

Every piece of government legislation is “sold” on the basis that it’s aimed to achieve certain results.

Instead of puffery, legislators should be required to specify the expected results in excruciating detail with a target date by which they will be achieved. In a reasonable time frame—say 18 months to three years maximum.

If those results are not achieved in the specified time, the legislation is automatically null and void. And the entire department in question is abolished.

This list hardly exhausts all the possibilities for improving the political process. Any other thoughts or suggestions? Please comment below.

By the way, if you think any of these suggestions are likely to be implemented in my lifetime or yours (pick whichever is longer) please send me a package of whatever you’ve been smoking. Must be really hot stuff.

Quite clearly, our Lords and Masters will be in no hurry to adopt any of these modest and highly reasonable proposals: that would entail reducing their powers over us, a proposition they will only be willing to accept under extreme duress.

So I’m not holding my breath and I suggest you don’t hold yours either.

Does your vote ever count?

Even if your vote is the decisive one, it still won’t count

“Politics, sex, corruption, blackmail, lies . . . and that’s just the first three pages!”

As teenagers, Alison and Derek were lovers—but chose opposite directions which tore them apart.Now adults, the pursuit of their incompatible dreams turns them into enemies who must deny their love for each other. But the real-world consequences of their actions bring them together in an alliance of mutual self-preservation—and cause them both to question their every belief.

Rave Reviews from Amazon Readers:

“This is one of the best books I have ever read.”

“Up there with The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. Powerful, intense, very well-written ”

“Mark Tier has a writing style as fluid as John Grisham’s or John Le Carre’s”

“Worthy of Ayn Rand . . . a spell-binding adventure ”

“Multiple plots, action great . . . and a nice touch of sex.”

See all customer reviews | Read the first chapter online | Download Part I in Kindle or epub format