The Conventional “Wisdom” on Market Risk is Just Plain BS

If it was right, NOBODY could beat the market. Not even Warren Buffett, George Soros, Carl Icahn, Jim Rogers, Bernard Baruch, or Peter Lynch!

Ever had your bank, broker, or financial planner ask you to fill out one of those risk assessment forms so they can determine your risk profile?

They ask questions like:

Do you want to make a lot of money?

Well, of course. Duh.

- They recommend a portfolio of high risk stocks.

Are you willing to take a lot of risk?

Of course NOT!

- They put you in the “risk averse” category and recommend a diversified portfolio.

Which option is riskier?

Which will make you richer?

A portfolio of high risk stocks means you have pretty much an even chance of making money—or losing it.

Might as well toss a coin.

A diversified portfolio means having tiny quantities of a whole bunch of different investments. If one of them goes up (or down) ten or twenty times, the effect on your net worth is almost zero.

Either way, there is no guarantee whatsoever that either of these investment strategies will make you rich. Indeed, as Fortune magazine once put it,

“One of the fictions of investing is that diversification is a key to attaining great wealth. Not true. Diversification can prevent you from losing money, but no one ever joined the billionaire’s club through a great diversification strategy.”

Nevertheless, these two options reflect the conventional wisdom about risk—that high profits are correlated with high risk, and vice versa.

If this is true, how can it be that Warren Buffett, George Soros, Carl Icahn, Bernard Baruch, Peter Lynch, Sir John Templeton, Kerr Neilson, and other well-known investors and speculators have regularly beaten the market over most of a lifetime?

Presumably, they followed the “high risk strategy,” and somehow managed to avoid significant losses.

The reality: absolutely not. Every single one of those investors I’ve mentioned is risk averse.

Their first priority is Capital Preservation.

To quote Warren Buffett:

Investment Rule #1: Never Lose Money

Investment Rule #2: Remember Rule #1

So how would Buffett, Soros, et. al. answer this question from HSBC’s risk assessment form:

3. On the whole, which of the following best describes your investment objective?

- a. Capital Preservation

- b. A regular stream of stable income

- c. A combination of income and capital growth

- d. Achieve substantial long term capital growth

- e. High capital appreciation

You can only click on one of those five answers. This is in keeping with the conventional “wisdom”: that it is impossible to be risk averse and beat the market regularly over time. (You can see the HSBC risk assessment questionnaire here)

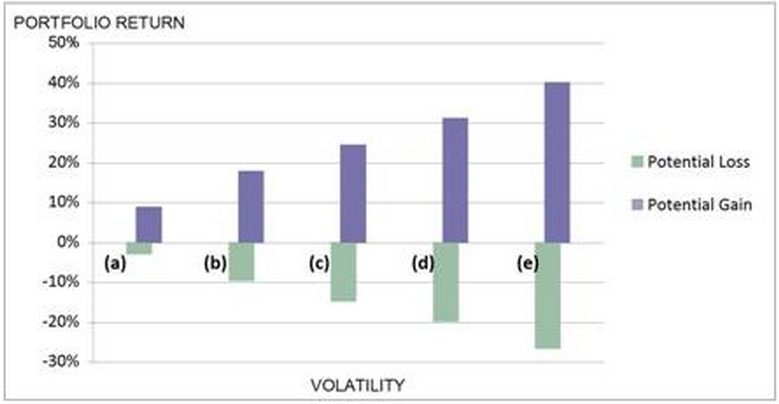

HSBC even illustrates range of returns of those 5 options with this picture:

Here, in a nutshell, is the Conventional “Wisdom” on risk—presented rather sneakily.

The purple bars are a little longer than the green ones, implying that each “strategy” will be profitable despite the risk. And that profitability will be about the same as the 9-11% long term average return on stocks—about the same as an index fund—regardless of risk.

Personally, if these are my choices I’ll take the index fund and go on vacation.

If the successful investor’s first priority is:

- a. Capital Preservation

and at the same time, his primary objective is:

- e. High capital appreciation

he wants to choose the impossible—according to the conventional ‘wisdom.”

Which implies that:

- 1. It’s impossible to beat the market; and,

- 2. Buffett, Soros, Baruch, Lynch et. al. cannot exist.

And it’s quite true that if you’ve succumbed to the Conventional “Wisdom,” it will be impossible for you to beat the market.

However, since Buffett, Soros, Lynch, et. al. do exist and have beaten the market, something is obviously wrong with the Conventional “Wisdom.”

And what’s wrong is the conventional view of risk.

The conventional view is right—when you DON’T know what you are doing.

What Risk Really Is

Consider something you probably do just about every day: get behind the wheel of your car.

Are you taking a risk?

The answer, of course, is yes. Some idiot can always do something that will involve you in an accident. So let’s rephrase the question to:

Are you taking the risk of causing an accident?

If you’re over 25, the answer to that question is probably not. By that age—at least according to the insurance companies—you have enough driving experience to be a pretty low-risk driver (to the insurance company).

If you think back to when you first got your learner’s license, how would you have answered that question?

No doubt, as teenagers think they are immortal, your answer at that time would have been a more emphatic “No!” than it would be today.

Looking back, you now realize that at age 16 you were an almost unguided missile threatening the life and limb of everybody else in the road.

What about this guy:

Is HE taking a risk?

“God, yes!” I can hear you thinking.

Fact is: we don’t really know. What we’re really feeling is: “If I were hanging off the edge of a cliff by my fingernails I’d be taking a risk.”

I don’t know about you, but I’d have fallen off long before anyone could have taken a picture of me like this. Assuming I ever got that far up the cliff.

But if this guy is an experienced mountain climber then he’s certainly taking far less risk than you or I would be. Perhaps no risk at all. He certainly looks pretty confident to me.

And why might he be confident? Because if he’s an experienced mountain climber then he knows what he is doing.

The truth is: risk is contextual

Risk is a function of whether or not you know what you are doing.

To quote from the legendary investor Bernard Baruch (who sold all his stocks before the crash of 1929):

“It is unwise to spread one’s funds over too many different securities. Time and energy are required to keep abreast of the forces that may change the value of a security. While one can know all there is to know about a few issues, one cannot possibly know all one needs to know about a great many issues.”

Jim Millner, former chairman of the Australian drugstore chain, Soul Pattinson, and a successful investor in his own right, put it far more succinctly:

“[The trustees] wanted me to diversify. Bugger that.”

So if diversification, as Buffett puts it, “is protection against ignorance” and “makes little sense if you know what you are doing,” how can the Master Investor make above average profits—nearly all the time?

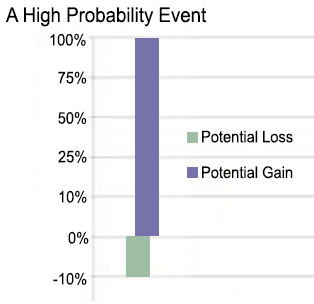

Simple (though far from easy): he specializes, and within his circle of competence looks for what’s called a High Probability Event.

As this picture shows, a High Probability Event is an investment with a low risk of loss and a high “risk” of profit.

And how does he find a “high probability event”?

By specializing in a tiny market niche, becoming expert within it—and spending almost all his time scouring that niche for a low-risk opportunity.

And when he finds one, he buys as much as he can.

The Master Investor puts all his eggs in a handful of baskets—and watches the baskets.

To put it another way, the conventional “wisdom” on risk is just plain BS.

F’rinstance, imagine our investment professional advising Bill Gates at the beginning of his career:

“Software and computers. Boy! Nobody knows whether they’ll ever amount to anything. You stand to lose your shirt. Think about a sideline with a steady income stream—supermarkets, to take one example—just in case.”

or Warren Buffett:

“You know, Warren, investing is a risky business. Everybody knows that. Perhaps you should think about diversifying into giving bridge lessons or something else, to be on the safe side.”

We both know that such advice is totally ridiculous.

Every successful business person succeeds by specializing. We both know intuitively that diversifying in business—starting two or more companies in totally different markets at the same time—is a recipe for disaster.

He who diversifies his activities—whether investing, in business or in life—is a Jack of All Trades and Master of None.

Every expert in a particular field acts from experience built on some 10,000 hours of single-minded “practice” in a tiny niche.

And as long as he stays there, he’s successful (and he keeps getting better).

The Grass Is NOT Greener On the Other Side

At dinner one night I met an investor named Larry who’s basically one-man in venture capital fund, specializing in biotech. Hearing Larry talk about the profits he’d made, the lady sitting next to me, Mary, said: “I’ve been thinking I should do something in the stock market. Maybe I should look into biotech.”

I asked what she’d invested in before. She’d been a real estate agent in New York for many years and had recently bought two condominiums that had since more than doubled in price.

All her friends and everyone she knew in the real estate business had urged her not to buy them. As reasons she was reminded of the litigation and internal disputes that were tearing the almost-bankrupt condominium association apart. With the low prices the condos were selling for offered as evidence of them being a lousy investment.

She knew better. That “these things will pass.” As they did.

I said to her: “Why do you want to know about biotech? Why should you even look at the stock market? You already know how to invest and make money. Why not do more of what you already know?”

For a moment, she sat there in a kind of stunned silence. And her face, her whole demeanor changed. The penny had dropped.

Mary already knew her wealth-creating niche.

She just didn’t know that she knew.

What Do You Know That You Don’t Know You Know?

Creating wealth is the result of specialization. Putting in that 10,000 hours to become a Master instead of a Jack of All Trades.

How to find what you know that you don’t know you know?

Go through your “money history.” Make a list with two columns.

- Column #1: where I’ve made money.

- Column #2: where I’ve lost it.

If you’re like Mary, always looking for “greener grass,” you, too will probably be surprised when you identify your circle of competence.

And as long as you stay within that circle of competence, you’ll know what you are doing.

Beware: Making Money Can Be Boring

That’s a statement that qualifies for Ripley’s “Believe it or Not”!

But—think of any successful business you’re familiar with. McDonald’s, for example.

How does McDonald’s make money?

By doing the same thing over and over and over and over and over again. Each repetition of those “billions served” adds a penny or a dollar to the bottom line.

But those pennies pile up into BILLIONS. Of dollars.

It’s thrilling to do something new and different. But when it comes to money, excitement takes you outside your circle of competence, which is usually hazardous to your wealth.

When tempted by the latest hot “tip” look in the mirror and repeat, until the temptation passes: “If I want excitement I’ll go skydiving.”

Putting in the time to truly understand and master a discipline—whether it be in investing . . . in business . . . or in life . . . is the best way to cut your risk, and grow your wealth.

Your Wealth-Creating “Circle of Competence”

How do you identify your circle of competence? Simply answer these questions:

- What am I interested in? What fascinates me?

- What do I know now?

- What would I like to know about, and be willing to invest the time, energy, and money to learn—and master?

The more detailed and specific you can be, the better. Then:

- Find a mentor—an expert in your field. You’ll learn a lot faster that way.

First published in Creating Wealth, November 2015

It is very encouraging to find so much of what I have internalized about investing reflected in Mark Tier’s works. I wish I had known this earlier, but I digress. Now there is still the constant work to execute better, become better and recover from all my earlier mistakes. Subsequently we have formed a family investment discussion group that is making a big difference in our collective results and is bringing the family ever closer together.

Hi Mark,

It’s great to receive an occasional blog post from you.

Your ‘investment habits’ book was hugely influential on my investment approach. It’s one I reread every couple of years.

I suspect I will approve of your ‘butt-sitting’ approach, once you have repaired the download link:-)

Rgds,